Elaboration on the 14 Obligations: Point 12

Remove barriers that rob staff and administrators of pride of workmanship and that rob students of the joy of learning. This means, inter alia, abolish staff ranking and the system of grading student performance.

This is the seventh in a series of blogs that translate Dr. W. Edwards Deming’s 14 Points for Management into the 14 Obligations for the School Board and Administration. In this essay we will expand on Point 12 of the following 14 Obligations. Some elaboration on this point was already provided in earlier blogs in this series that addressed Points 2, 3 and 5 through 11. It is yet another illustration that the 14 Obligations are not a “cafeteria plan.” They are intimately, intricately interwoven in a complex fabric of a healthy environment for work, learning and continuous improvement.

Obligations of the School Board and Administration

- Create constancy of purpose toward improvement of the entire school system and its services.

- Adopt the new philosophy. We are in a new economic age.

- Cease dependence on tests and grades to measure quality.

- Cease dependence on price alone when selecting the curriculum, texts, equipment and supplies for the system.

- Improve constantly and forever every process for planning, teaching, learning and service.

- Institute more thorough, better job-related training.

- Institute leadership (i.e., management of people).

- Drive out fear.

- Break down barriers between groups in the school system.

- Eliminate the use of goals, targets and slogans to encourage performance.

- Closely examine the impact of teaching standards and the system of grading student performance.

- Remove barriers that rob staff and administrators of pride of workmanship and that rob students of the joy of learning. This means, inter alia, abolish staff ranking and the system of grading student performance.

- Institute a vigorous program of education and self-improvement for everyone in the system. Don't forget the needs of parents.

14. Plan and take action to accomplish the transformation.

The essence of Point 12 calls for the elimination of annual ratings for staff and abolishing the system of grading student performance. This is not to suggest that leaders no longer provide feedback to staff members and students; quite the opposite. Unfortunately, traditional practices of appraisal and grading – which this point calls to abolish – fail to provide helpful feedback.

After all, what is a grade? More than half a century ago, Michigan State University’s Paul Dresser defined it as follows: “A grade is an inaccurate judgment by a biased and variable judge of the extent to which a student has attained an undefined level of mastery of an unknown proportion of an indefinite amount of material.”1

As in the case of Point 3’s treatment of standardized tests, this point does not call for the elimination of assessment; only that leaders recognize that test scores and other outcomes are produced by work and learning processes – not the people alone. Hence, when conducting reviews with workers, emphasis must be placed on planning and development for the future, as opposed to just grading or evaluating past performance.

Many administrators are saddled with state-mandated systems that emphasize teacher appraisal and ranking, often to the detriment of coaching and development. (Some are so burdensome that districts must seek additional state funding to hire per-diem evaluators!2) Such practices too often prove to be barriers to staff members feeling good about themselves and their work. Instead of solid plans for training and development (Points 6 and 13), traditional appraisal practices generate resentment and fear (Point 8). Later, when the evaluations are used to drive individual recognition and reward systems, teamwork suffers (Point 9).

Questions to Ponder When Coaching Employees

Leaders in the short term can shift their staff reviews from a mode of appraising past performance to one of coaching and planning for future development. Even with current systems for ranking, during review discussions leaders can collaborate with their employees to seek and take action on answers to the following questions.3

♦ Do I know what this person must do in order to succeed in this job?

• Who are the user/customers of the results and outputs of this job?

• What do the customers need in order to best use the results of this job?

• Who supplies the inputs to this job? Are those inputs suitable for use?

♦ Have I discussed the above with this employee so that there is a clear understanding of

what he or she needs to do?

♦ Have I provided this employee with the necessary resources to do this job well (tools,

training, time, equipment, information, good material, and so on)?

♦ What does this person see as the major barriers to doing this job well? What have I

done to remove those barriers?

♦ Have I asked what this employee needs from me to do this job well?

♦ Do I know this person’s needs as an individual?

♦ Am I acting as a coach and a teacher in this review, as opposed to simply grading past

performance?

♦ Have I provided opportunities for in-depth discussions with this person about this job

and its objectives?

With minor editing, these questions could be restated as questions to ponder when coaching students (and their parents). Action taken on answers to these questions will provide for much greater development of the organization’s human resources than any traditional grading or appraisal system ever could.

Radical – But No Less Rational

An earlier blog in this series made reference to the following observation from one of Deming's texts: “Abolish grades (A, B, C, D) in school, from toddlers on up through the university. When graded, pupils put emphasis on the grade, not on learning…. The greatest evil from grades is forced ranking – only (eg.) twenty percent of pupils may receive an A. Ridiculous. There is no shortage of good pupils.”4 But how do I know how my children are doing in school without grades? How do my children get into college without grades? To propose that we abolish them is so radical!

On the surface, this element of Point 12 seems radical; but viewed through the lenses of rational theory of variation makes this radical proposal no less rational. Some knowledge of theory of variation leads to the understanding that the question is not whether or not student achievement levels are different. They’re going to be different. The question is, “Are those achievement levels significantly different?” If the performance or achievement levels are significantly different, then treat, grade and reward those students differently.

If the performance or achievement levels are not significantly different, don’t treat or reward them differently. Why? Because the limits we use to test for significance are dictated and controlled by common causes of variation from within the process of which students are but a part – and students can perform no better than the process allows! Why do we persist in issuing low grades to students when it’s so often the system that’s failing?

Knowledge of the theory of variation is required to fully grasp the dangers of traditional grading practices in our schools. In this regard, Deming wrote, “Need a teacher understand something about variation? Mr. Heero Hacquebord sent his six-year-old daughter to school. She came home in a few weeks with a note from her teacher with the horrible news that she had so far been given two tests, and this little girl was below average in both tests…. The little girl learned that she was below average in both tests. She was humiliated, inferior. Her parents put her into a school that nourishes confidence. She recovered.”5

Fortunately, the little Hacquebord girl’s story had a happy ending. How many students’ stories have a sad or tragic ending because they have teachers who do not possess some knowledge of the theory of variation?

Knowledge of Theory of Variation Can Save Children: A Case Study

A few years ago, a school superintendent from California attended one of my seminars on applying statistical methods to teaching, learning and administrative processes. The day he returned to his district, the report of his first graders’ reading test results landed on his desk.

The report showed the number of words that first graders read correctly in a 100-word story. More specifically, it listed by student and classroom the actual number of words the first graders read correctly in the district’s twelve first-grade classrooms. The results ranged from 0 to 100 words read correctly. Students who read below a certain number of words correctly were identified for Chapter 1 (remedial reading) help and were provided that help.

To his test data, the superintendent applied some of the intermediate, analytic statistical techniques that he had learned in my seminar. His analysis indicated that most of the first-graders in his district fell into a group that constituted a system. In other words, their test scores were different but they were not significantly different. They rolled the reading program and test dice, and they all rolled somewhere between a 2 and a 12, inclusive. No students achieved significantly high scores.

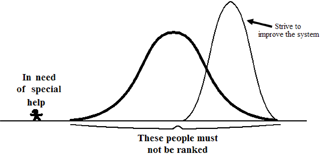

In some of the classrooms, however, a few students’ scores fell statistically significantly low in comparison to all of the other test scores. They rolled the reading program and test dice and got a negative number! This would indicate that these students were in need of special help (see figure below), like that provided by Chapter 1 or “Reading Recovery” or similar programs. But three out of every four students in the district who needed the special help were not receiving it! The (arbitrary) standard for Chapter 1 assistance had been placed at a score that was lower than theirs.

Bear in mind that norm-referenced standards, such as those applied to identify students for Chapter 1 assistance, are often derived from national or state scores. But this leader was not the superintendent of schools for the United States of America nor for the State of California. He was superintendent of schools in his own town. The norm-referenced standards had dictated who among his children would receive help and who would be denied that help. Only when he applied the analytic statistics to his own first graders’ raw scores was he able to remove the barrier imposed by the standard. Only then was he able to understand the variation in his own district and understand the needs of his own unique first-graders.

Figure. Students whose scores plot significantly low are in need of special help.

In the absence of this understanding, tragically three out of every four students in need of special help remained in their regular classrooms – in need of special help, but not getting it. When the superintendent called me to report his findings, he said he felt physical pain as a result of what he’d learned. He realized that those first-graders were sitting in their regular classrooms, falling farther and farther behind in their language development. They were sitting in their regular classrooms, not understanding why they couldn’t keep up; not understanding why they were failing. (He immediately took action to place those students in the Chapter 1 program.)

What struck the superintendent like a bolt of lightning was the realization that at the tender age of a first grader, within a few short years they would have been lost! His voice cracking, he said to me, “It’s devastating to realize that I have spent most of my career hurting children.”

He hadn’t meant to hurt children. He hadn’t meant to fail to provide special help to children in need of special help; just as I’m sure the little Hacquebord girl’s teacher hadn’t meant to humiliate her and make her feel inferior. But because he lacked knowledge of theory of variation, he indeed ended up spending the bulk of his career hurting kids.

Now this problem is not a people problem. I do not blame this superintendent or other educators for their lack of knowledge. It’s not his fault that he was awarded undergraduate and graduate degrees and his doctorate from the University of California at Berkeley with no knowledge of rational theory of variation. It is a fault of the system, and the costs are devastating. The costs are incalculable because they involve our children and their futures.

How many so-called reform mandates have called for widespread study and understanding of theory of variation? Clearly, we do not need reform; we need transformation. Without transformation – without a change in state, without understanding the destructive effects of our obsession with grading and ranking and evaluating and appraising people – well-meaning and caring educators will continue trying their best to help children, but only end up hurting them.

In closing, consider the following entry in a student’s learning log at the high school in Ware Shoals, South Carolina: “The work required is our best, so when we give it, we pass. I truly like that. Because sometimes our best is not always so good. We are able to concentrate on learning and teamwork without thinking of grades and the competition that goes along with them.”

Conclusion

In our expansion and elaboration of the twelfth Obligation of the School Board and Administration, we made reference to Points 2, 3, 5 through 11 and 13. In other words, we cannot talk about Point 12 without at the same time talking about ten of the remaining 13 Points. As noted at the beginning of this essay, this clearly illustrates that the 14 Points are not a cafeteria plan. They are indeed intricately, intimately interwoven into a complex model of a healthy environment for work, for learning and for continuous improvement. The next and last blog in this series will elaborate on Points 13 and 14. I hope you are enjoying these blogs and will share the information with educators in your community.

Notes

1P. Dresser in Basic College Quarterly, Michigan State University, Lansing, MI (Winter, 1957), p. 6.

2A. Shea, “Teacher Evaluation Program May be Burdensome for Staff,” Norwich Bulletin, Norwich, CT (April 14, 2013), p. A1.

3Derived from “Deming’s Point Seven: Adopt and Institute Leadership,” Commentaries on Deming’s Fourteen Points, Ohio Quality and Productivity Forum, Piqua, OH (1989), pp. 4-5.

4W.E. Deming, The New Economics for Industry, Government, Education, MIT Center for Advanced Educational Services, Cambridge, MA (1994), p. 148.

5W.E. Deming, Out of the Crisis, MIT Center for Advanced Educational Services, Cambridge, MA (1986), p. 130.

© 2013 James F. Leonard. All rights reserved. www.jimleonardpi.com.